This historical drama about the revolutionary best known today as Udham Singh has a powerful climactic scene set in the wake of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Unfortunately it’s a slog getting there.

How does one depict something as horrifying and as chaotic as the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre – one of the major imperialist crimes of the last century – in a narrative film? It has been done before, of course, and the cinematic possibilities are obvious – but how to do it authentically, unflinchingly, yet without making it seem gratuitous, and preserving some respect for the victims (even if most of them – screaming, jostling past each other, falling to randomly directed bullets, jumping into a well – weren’t given that dignity in real life)?

Watching the long climactic sequence of Shoojit Sircar’s Sardar Udham – the story of the revolutionary who assassinated a former Punjab lieutenant governor in London in 1940, as revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh carnage – is to realise that as much can be done with the aftermath of the massacre as with the actual killing. Around three-fourths of the way through this long and often inert film comes this deathly still vision of hell, among the bleakest that mainstream Hindi cinema has given us. The tragedy has unfolded: with the British general shouting orders, people screaming, bullets ripping bodies apart, leaving severed limbs in their wake. And then, when it is over, the young Sher Singh (Vicky Kaushal) finds himself on the site, trying to process the enormity of what has happened while also trying to save as many of the still-living as he can.

From the images of the wounded dragging themselves back home if they could, to the ones of Sher Singh retrieving bodies, this scene becomes more compelling through the prolonged repetitiveness of some images: the young man wading through gore, looking for signs of life, lifting people onto his small cart, wheeling them to the small makeshift medical centre; and then again, and again, and again.

The sequence as a whole serves two functions: one, to reclaim Jallianwala Bagh from dry textbook accounts and our dulled sepia-tinted impressions, and convey something of what it must have felt like to be there. (In its conception, the scene reminded me of the famous opening sequence of Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, which presents a ground-level view of the 1944 Normandy landing.) And two, to provide a full sense of how Sher Singh’s life changed shape and direction: the transformation of a 20-year-old in the middle of his most carefree years into a man with a single, life-consuming purpose.

However, as powerful as these Amritsar scenes are, the question is: do they come too late in a generally flabby, uneven film? The main reason why I had stuck with Sardar Udham till this point was because I was reviewing it; it is easy to imagine regular viewers getting distracted and bored and switching off midway through.****

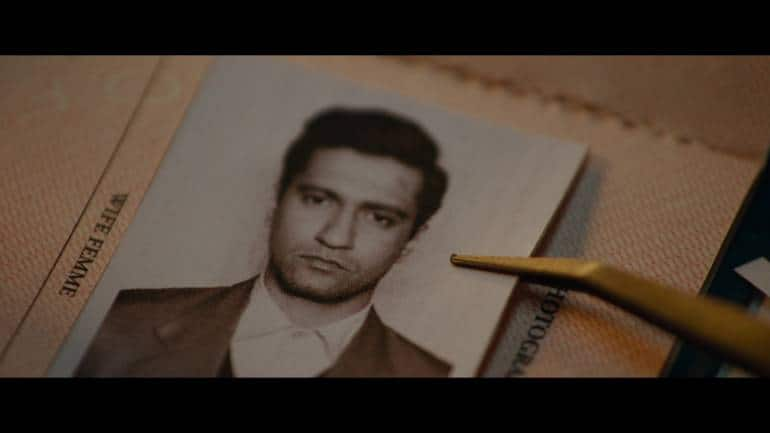

Sardar Udham opens with Sher Singh – later known as Ude and Udham as he uses various aliases and passports – being released from prison in India in 1931 (he was incarcerated because of his revolutionary activities, including illegal arms possession). We see the single-mindedness of someone who has no further need of ordinary life. (“Sab ne phanda hee choomne hain na?” – “You all yearn for the noose” his cousin says when he briefly returns home.) This is followed by glimpses of his journey to England via the USSR, along with vignettes from his past, including his participation in the HSRA (Hindustan Socialist Republican Association). At this point the film is as much a travelogue as anything else, with circumstances and personality leading a man into a much wider world than the one he was born into.

In London, Udham establishes contacts with other Indian freedom fighters and socialists, searches the phone book for his target – Michael O’Dwyer, who had facilitated the Jallianwala Bagh firing – and seethes inwardly as British radio refers to “the Amritsar affair of 1919”. The story abruptly leaps ahead a few years to show the assassination (all this within the first half-hour) and then the film returns to its restless, searching, non-linear structure. While he is interrogated and tortured in prison, we see more flashbacks: comradeship with Bhagat Singh (Amol Parashar) in Lahore; a hesitant romance with a mute girl (the second time, after October, that Banita Sandhu has played a silent cipher in a Shoojit Sircar film, though thankfully Sardar Udham steers away from making her character the main reason for Udham’s thirst for revenge). There are also scenes depicting his years in London leading up to the killing of O’Dwyer, including a connection – tenuously depicted – with a British woman named Eileen, and with the Irish Republican Army. (“You lamb, me lamb. Butcher same.”)

For much of its running time, it feels like the cold damp atmosphere of London has pervaded the film itself. The heat and dust and boisterousness of Udham’s Punjab are nowhere to be found in these scenes (except maybe in a little moment where an excited Udham exclaims “Tussi jaande ho?! (You know him?!)” at a British woman when she mentions Bhagat Singh’s name) – and this is understandable, since part of the point being made here is that this young man has had to travel far from his roots; to get revenge on behalf of the land he loves, he has had to make the sacrifice of moving away from that land to a cold, culturally remote place and trying to fit in there. This is an especially poignant aspect of the Udham Singh story – one that separates him from the freedom fighters who stayed in India and died on their own soil – and the film does a decent job of suggesting it.

The point is also made early on that Udham isn’t concerned so much with big-picture equality or justice as with the specific matter of his country’s enslavement: if as an Indian he isn’t free, then how can he march with free people seeking other forms of equality and campaigning for other social causes, he says. But if he is focused and pragmatic, Sardar Udham soon becomes very diffused in its bird’s-eye view of history – at times it feels like it is seduced by its own scale. Despite its visual elegance and the believability of the art design and period detailing (or even because of these things), it starts to play like a protracted history lesson weighed down by the need to engage with everything going on at the time: WWII, the realpolitik between Britain, Russia and Germany, the IRA conflict. There are conversations between Winston Churchill and King George VI, between O’Dwyer and General Reginald Dyer, that are well-staged but scarcely serve the narrative’s purpose.

At one point it even feels like the man at the centre of the story is in danger of being forgotten. There isn’t much access to Udham’s inner state of mind, notwithstanding a couple of scenes (one in a courtroom, one with a tramp in Hyde Park) where he delivers pedantic and flat-sounding speeches about freedom. Here and elsewhere, Vicky Kaushal gets to seethe and rant but with no real character arc to assist him, just a few disconnected moments that are meant to add up to a sympathetic life. By the time we arrive at the (invented) subplot about Udham working for O’Dwyer as an all-round handyman, with a conversation between the two that makes sense only as a fever-dream, cinematic energy has gone out the window.

It returns, as indicated above, with the 1919 Amritsar sequence where the film’s deliberately slow pacing is finally put to powerful use and Kaushal gets to bring his acting chomps to a scene that deserves it. There is, of course, much dramatic licence here – the staging makes it seem like Udham was almost the only person helping the wounded for hours after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre – but a certain amount of drama is a welcome relief after all the stiff-upper lip coolness that came before. And the image of a young Sikh boy moving numbly through a sea of dead and wounded, trying mechanically to help, barely realising how much he has already been changed by this experience, is a very striking one. But again, does this climax vindicate the static earlier sections of the film?

Paradoxically, Sardar Udham manages to be both a quiet, minimalist film (if you watch its individual scenes in isolation) AND a bloated one (in terms of its overall narrative arc). As a fan of Sircar’s earlier work, especially his films with Juhi Chaturvedi – the lean, to-the-point storytelling of Piku or Vicky Donor or October – this was disappointing; this could easily have been a shorter film while retaining everything necessary to tell its story and without sacrificing its measured pace. Or, given its level of ambition, maybe it should have gone for a different format and been a series instead.

A footnote

More than 50 years ago, in London in 1970, Hrishikesh Mukherjee shot parts of a film titled Man from India, with Parikshit Sahni in the lead as Udham Singh. It was a prestige project with contributions by Utpal Dutt and Parikshit’s father Balraj Sahni, and might have been a fascinating work if it had achieved the stately, novelistic quality of Mukherjee’s recent Satyakam. Unfortunately the film was shelved for reasons that are unclear; years later, one of its producers managed to cobble together a version with some star value provided by Vinod Khanna (in a supporting role but top billed) – it was eventually released as Jallian Wala Bagh and sank without a trace despite a few points of interest such as Gulzar in an acting part as Udham Singh’s friend who points out Michael O’Dwyer to him in London.

While it is pointless to speculate about what Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Udham Singh film would have looked like, it’s safe to assume that it would have been very different in tone from Sardar Udham, which belongs to a much more restrained, detail-extensive and outwardly polished filmmaking culture.